A Critical Look at Claims for Green Technologies

Green technologies are not yet proved, affordable, or deployable—but even if they were, it would still take them generations to solve our environmental problems

When a bright new idea comes along, it’s easy to imagine a fantastic future for it. Perhaps the best example of this is Ray Kurzweil’s Singularity, scheduled to arrive in 2045, which will supposedly bring “immortal software-based humans, and ultra-high levels of intelligence that expand outward in the universe at the speed of light.” Not to be left behind, a former Google X senior executive says that “everything you see in sci-fi movies is going to happen.” Not just something, mind you, but everything.

Compared with such utterly ahistorical visions, unmoored from reality, the articles gathered in this issue are actually quite tame. They promise only a long-lasting supply of affordable and clean energy—either through nuclear fission or through electricity derived from burning (yes, burning) CO2—and a surfeit of food from a variety of sources: vertical farms based in cities, crops that will need almost no fertilizer, and environmentally friendly meat substitutes.

Of course, these claims of impending innovation may be seen (although they are not labeled as such) as being largely aspirational—but the benefits would be great if even just a fraction of their goals were realized during the next generation.

At the same time, these claims should be appraised with unflinching realism. I would not presume to offer specific, in-depth critiques of proposed innovations even if I had 300 instead of three pages to work with. Instead, I will just point out some nontrivial complications pertaining to specific proposals, and above all, I will stress some fundamental systemic considerations that are too often ignored. These are not arguments against the need for some form of the techniques that are promoted here but rather cautionary reminders that many of today’s ambitions will not become tomorrow’s realities. It’s better to be pleasantly surprised than to be repeatedly disappointed.

Human beings have always sought innovation. The more recent phenomenon is this willingness to suspend disbelief. Credit this change to the effect that the electronics revolution has had on our perceptions of what is possible. Since the 1960s, there has been an extraordinarily rapid growth in the number of electronic components that we can fit onto a microchip. That growth, known as Moore’s Law, has led us to expect exponential improvements in other fields.

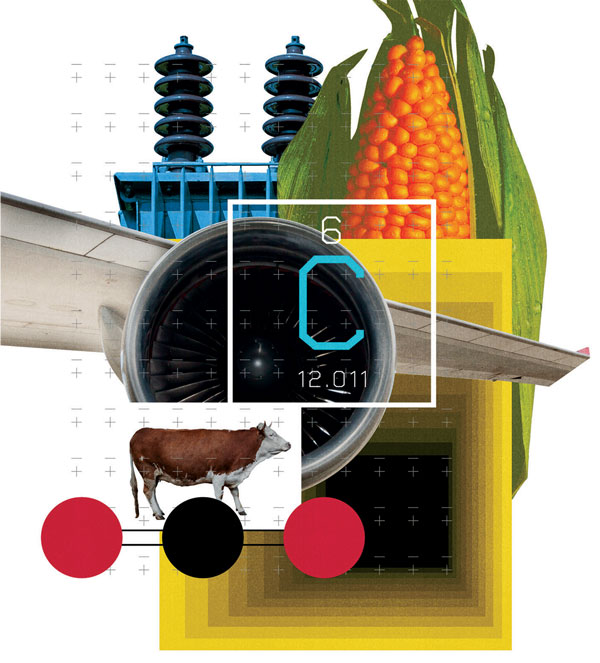

However, our civilization continues to depend on activities that require large flows of energy and materials, and alternatives to these requirements can’t be commercialized at rates that double every couple of years. Our modern societies are underpinned by countless industrial processes that have not changed fundamentally in two or even three generations. These include the way we generate most of our electricity, the way we smelt primary iron and aluminum, the way we grow staple foods and feed crops, the way we raise and slaughter animals, the way we excavate sand and make cement, the way we fly, and the way we transport cargo.

Some of these processes may well see some relatively fast changes in decades ahead, but they will not follow microchip-like exponential rates of improvement. Our world of nearly 8 billion people produces an economic output surpassing US $100 trillion. To keep that mighty engine running takes some 18 terawatts of primary energy and, per year, some 60 billion metric tons of materials, 2.6 billion metric tons of grain, and about 300 million metric tons of meat.

Any alternatives that could be deployed at such scales would require decades to diffuse through the world economy even if they were already perfectly proved, affordable, and ready for mass adoption. And none of the innovations presented in this issue fits fully into that category. In fact, these three critical prerequisites are notably absent from nearly all of the innovations presented in this issue.

Most of the articles do acknowledge that difficulties lie ahead, but the overall impression is one of an accelerating advance toward an ever more remarkable future. That needs some tempering. Today, we can fly for up to an hour in a two-seat, battery-powered trainer plane; in a decade, perhaps we’ll fly in a battery-assisted regional hybrid plane. The savings in energy use and in carbon emissions will be modest—and we are a very long way from all-electric intercontinental airliners. [READ MORE]