The Engineer’s Guide to AI: Decoding PINNs with Undergraduate Math

By: A Fellow Math Enthusiast

Target Audience: Bachelor of Engineering Graduates & Calculus Lovers

Introduction: Your Degree Was Not in Vain

If you are an engineer who sat through years of Calculus, Linear Algebra, and Differential Equations wondering, “Will I ever actually use this?”—the answer is a resounding yes.

We are currently witnessing a revolution in computational engineering called Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). While the term “Neural Network” sounds like computer science magic, the engine under the hood is pure, classical engineering mathematics.

This article breaks down how the subjects you religiously studied in your bachelor’s degree are the exact building blocks needed to solve the complex mathematical problems of modern AI.

What is a PINN? (The Engineering Hook)

In traditional engineering (like Finite Element Analysis), we solve Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) by creating a “mesh” (a grid) and approximating derivatives numerically. If the mesh is bad, the simulation crashes.

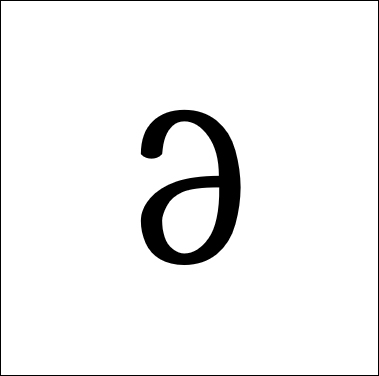

PINNs differ fundamentally. They treat a Neural Network as a Universal Function Approximator. We assume the solution to a physics problem, u(x,t), can be approximated by a continuous function û parameterized by weights parameter(θ).

The “magic” is that we force this network to satisfy two things simultaneously:

- The Data: It must match known boundary conditions.

- The Physics: It must satisfy the governing PDE at every point in the domain.

Here is the syllabus you need to master this technology.

- Multivariable Calculus (Calc III)

The Component: Automatic Differentiation

In your degree, you learned the Chain Rule: dz/dx = (dz/dy) ⋅ (dy/dz)

In PINNs, this is the most critical tool. When we need to calculate a derivative like ∂u/∂x to check if our physics holds true, we do not use approximate slope formulas. Instead, we use Automatic Differentiation.

The software recursively applies the Chain Rule through every layer of the neural network (which is just a composite function) to calculate the exact derivative of the output with respect to the input coordinate. If you understand the Chain Rule, you understand the engine of a PINN.

- Differential Equations (ODEs & PDEs)

The Component: The “Loss” Function

You remember solving the Heat Equation or the Wave Equation. You learned that these equations equal zero when balanced.

u_t – α u_{xx} = 0

In Deep Learning, we train networks by minimizing a “Loss” (error). In a PINN, we define the error as the residual of the PDE.

If the network outputs a solution where u_t – α u_{xx} = 0.5, the “Physics Loss” is 0.5^2. The network then adjusts its weights to drive that residual closer to zero. Your understanding of Homogeneous/Non-homogeneous equations and Boundary Conditions (Dirichlet vs. Neumann) is directly used to write these error terms.

- Linear Algebra

The Component: The Architecture

A neural network is often described as a “black box,” but to you, it is just Matrix Multiplication.

A single layer in a network is simply:

y = \sigma(Wx + b)

Where W is a matrix of weights, x is your input vector, and b is a bias vector.

Deep Learning is essentially performing a series of affine transformations to map inputs to outputs in a high-dimensional vector space. Your knowledge of dimensions, dot products, and vector spaces is what allows you to visualize how the data moves through the model.

- Optimization Theory

The Component: Training the Model

How does the network get better? We use Gradient Descent.

Imagine a 3D surface representing the “Error.” We want to find the lowest point (minimum error). We calculate the Gradient (\nabla), which points steeply uphill, and we take a step in the opposite direction.

Engineers often use advanced optimizers like L-BFGS (Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno). This is a Quasi-Newton method you might have seen in Operations Research. Because PINNs require high precision to satisfy physics, standard AI optimizers (like Adam) are often not enough; we need the heavy artillery from classical optimization theory.

- Numerical Methods

The Component: Validation

You likely learned the Finite Difference Method (FDM) or Runge-Kutta. In the world of PINNs, these “old” methods are still vital. They provide the Ground Truth. To prove a PINN works, you must compare it against a standard numerical solution. Your ability to code a quick FDM solver allows you to validate if your fancy AI is actually respecting the laws of physics or just hallucinating.

Summary: The Syllabus Map

For the engineer who loves math, the path to AI is not about learning a new field from scratch. It is about re-contextualizing what you already know.

| Your Bachelor’s Subject | The AI Implementation |

| Multivariable Calculus | Automatic Differentiation (The Engine) |

| Partial Diff Eqs | The Physics Loss Function (The Constraint) |

| Linear Algebra | The Neural Network Layers (The Structure) |

| Optimization Theory | L-BFGS / Gradient Descent (The Training) |

| Numerical Methods | Validation & Collocation Points (The Proof) |

The bridge between “Engineering” and “AI” is built on the mathematics you have already mastered. You just need to walk across it.

Comments :