Velocity-Based Training (VBT) Sensors: Lifting by Speed, Not Just Weight

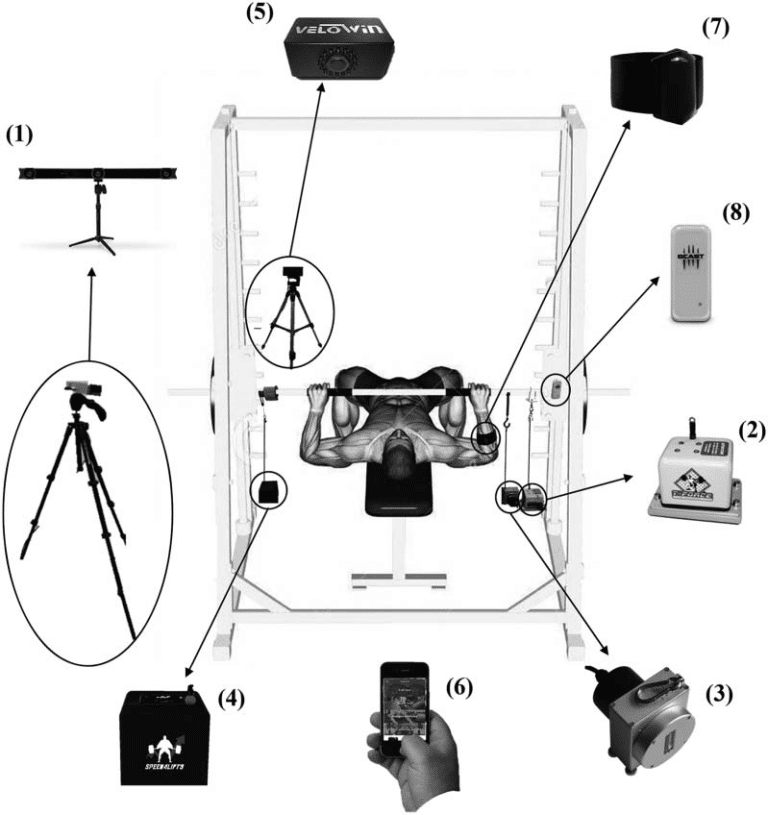

Velocity-Based Training (VBT) was once the secret weapon of Olympic weightlifters, but it became accessible to the general market with the release of consumer-friendly sensors like Push (2013) and affordable apps compatible with Vitruve (circa 2018). These small devices attach to a barbell or dumbbell and measure exactly how fast the weight is moving in meters per second. This shifted the focus from “how much” you lift to “how well” you lift it.

The main problem VBT sensors solve is the inaccuracy of “Percentage Based Training” (PBT). Traditionally, workout programs ask you to lift a percentage of your “One Rep Max” (e.g., lift 80% of your max). However, a person’s strength fluctuates daily due to sleep, stress, and nutrition. 100kg might feel light on Monday but impossible on Friday. Sticking rigidly to a fixed number often leads to “junk volume” (training too light) or injury (training too heavy when fatigued).

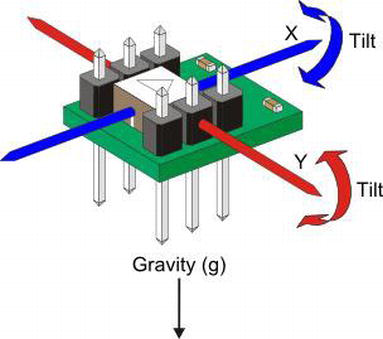

VBT sensors make the lifting world better through “autoregulation.” The sensor tells you the truth about your body’s readiness. If you are trying to build explosive power, the app might tell you, “Your speed dropped below 0.8 m/s, stop the set.” This ensures that every single repetition performed is of high quality and targets the specific athletic trait (strength, power, or hypertrophy) intended. It removes the ego from lifting and replaces it with physics. Take a VBT using a IMU sensor for example. At its core, an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) works by using microscopic electromechanical systems (MEMS) to translate physical motion into digital data. Inside the tiny chip, there are silicon structures suspended on microscopic springs that act as proof masses; when you move the device, inertia causes these masses to lag behind the casing, slightly shifting their position. This shift changes the distance between tiny capacitor plates, altering the capacitance, which the chip detects and converts into a voltage signal. By measuring linear force (via the accelerometer) and rotational velocity (via the gyroscope) simultaneously, the IMU’s onboard processor fuses this raw data to calculate the device’s exact orientation, velocity, and gravitational load in three-dimensional space, thousands of times per second.

The data proof is compelling, particularly in injury prevention and power development. Studies and user data have shown that stopping a set when velocity drops by 20% yields similar or better strength gains than training to total failure, but with significantly less fatigue and recovery time required. Teams using VBT have reported reductions in soft-tissue injuries because players are never forced to grind out reps when their nervous system is already exhausted. It provides a tangible “stop sign” that protects the athlete.

Comments :